Montparnesse and Saint Germain-des-Prés Café gatherings

salon culture

Since the late 17th century, the cafés of Paris have been fertile ground for art, literature, philosophy and politics, places where a president, an avant-garde poet, a handful of artists, an anarchist and everyday people are seated at adjoining tables. There was and still is nothing exclusive about these places and that is their strength. Writers and artists living and working in Paris always frequented cafés, not just for the social aspects, but also as a warmer and more pleasant respite from their tiny studios and apartments.

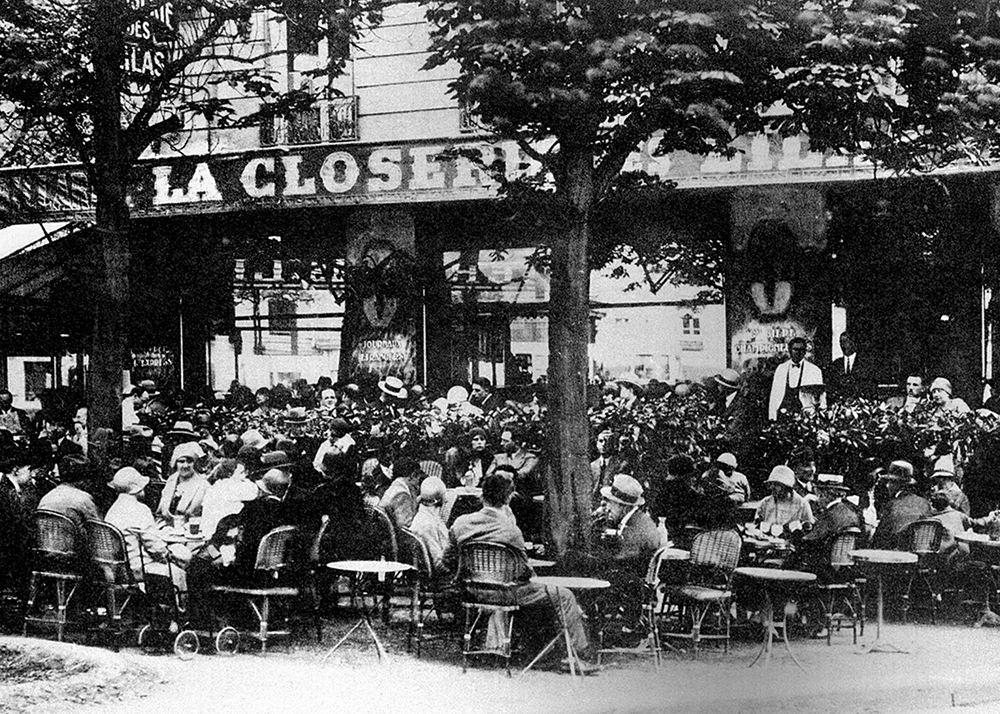

By the end of the first decade of the twentieth century, the brand-new neighbourhood of Montparnasse was a work in progress, with wide streets and empty lots; perfect for the blossoming Modernists. A ring of new, large cafés at the intersection of Boulevard du Montparnasse and Boulevard Raspail became the favoured places to gather and and town square for a growing avant-garde community.

Since the artists and writers of Montparnasse often lacked amenities in their studios, co-mingling with each another in cafés such as the Dome, the Coupole, the Rotonde, and the Select were first made popular by a clique of German intellectuals who became known as the ‘Domiers’ comprised of Wilhelm Uhde, Richard Goetz, and Alfred Flechtheim. Austrians, Russians, Scandinavians, and Americans all followed the Germans to Montparnasse. Modigliani arrived 1909. Picasso in 1912.

This co-mingling of artists, French writers and American expats, who lived and occasionally worked in the cafés such as Closerie des Lilas–located on the corner of Boulevard du Montparnasse and Boulevard St. Michel–included an eclectic mix of artists, dancing girls and patrons of teh nearby ballroom. Emile Zola brought his friend Paul Cézanne. Paul Fort, the French poet was often seen playing chess with Lenin on the terrace and every Tuesday, at five o’clock, in the large ground-floor salon he would gather his friends around him–fellow writers and poets–to challenge each other’s opinions, exchange poems and read poetry all fuelled with absinthe. Five o’clock was often called ‘the green hour.’

La Closerie’s Tuesdays became an international meeting-place of ideas including Modigliani, André Breton, Aragon, Van Dongen, Jean-paul Sartre, André Gide, Paul Eluard, Oscar Wilde, Samuel Beckett, Man Ray and Ezra Pound and others.

Picasso was introduced to the Closerie des Lilas by Guillaume Apollinaire in 1905. Fernande Olivier, Picasso’s companion, described it in her memoir as, “Hubbub, uproar, madness.”

La Closerie des Lilas is where Ernest Hemingway would go to write for the Toronto Daily Star, for which he was as a foreign correspondent, and it was the first place he read his friend and fellow expat F. Scott Fitzgerald’s manuscript of The Great Gatsby. It was while he lived in Paris that Hemingway decided to begin writing novels with his first The Sun Also Rises written in Paris in 1926.

An elated James Joyce spent a memorable evening at the ‘Closerie’, celebrating the news that Sylvia Beach publisher and owner of the iconic bookstore Shakespeare and Company agreed to publish his controversial novel Ulysses. Gertrude Stein and her life partner, Alice B. Toklas, also regularly visited the café.

Shakespeare and Company, part bookstore-part cafe, was a favoured place for English and American expatriates and exiles to meet, particularly Hemingway, Henry Miller, and Scott Fitzgerald, the men Gertrude Stein had dubbed the ‘Lost Generation’.

French writers such as Jules Romains were also drawn by the compact yet fine selection of books by American writers.

Beach hosted readings of both published works and works in progress at Shakespeare and Company and operated it as a lending library in addition to helping struggling writers with work, food or a bed. She made significant contributions to literature by championing and selling the works of little known or banned authors.

The store was also a haven for writers unable to find a publisher. In 1920 Beach attended a party at the home of the poet Andre Spire, which was a welcome party for the Irish writer James Joyce, at the start of his 20 years of self-imposed exile in France. Joyce it turned out had a manuscript he wanted printed. It had been serialised previously in parts, in the US in 1918-20, but was rejected by book publishers. The manuscript was Ulysses. Beach published the first edition in 1922.

During the great depression Shakespeare and Company struggled to say viable and was forced to close when the Germans occupied Paris in 1941 after Sylvia refused to sell her last copy of Finnigan’s Wake to a high-ranking German officer and it was decreed the store was to be closed and all the goods confiscated. Sylvia moved everything to the apartment and painted over the sign. She was Beach interned for six months and spent the rest of the war keeping a low profile.[1]

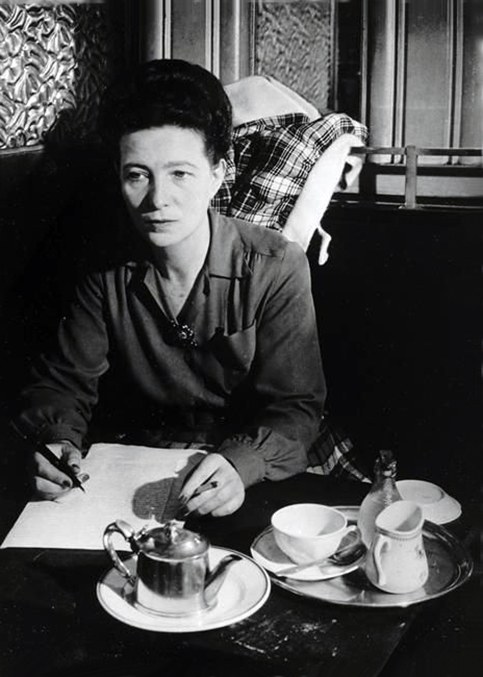

After the Second World War, the loci of intellectual discourse moved down the boulevard to St-Germain-des-Prés, where Sartre and de Beauvoir wrote at the café tables of Le Deux Magots and Café de Flores.

It was 1939 when the new manager of the Café de Flore, located at 172 boulevard St-Germain, installed a larger, more powerful coal-fired heater to warm the establishment. Not only did the new heater warm the ground floor, it also warmed the much quieter first. Simone de Beauvoir, who previously frequented the Dôme, in Montparnasse, established herself at one of the dozen tables on the first floor. Apollinaire used the ‘Flore’ as his office, the surrealists showed up, as did Trotsky and Zhou Enlai and fellow existentialists Albert Camus, Raymond Aron, Maurice Merleau-Ponty.

Less popular at the time, the Saint-Germain-des-Prés cafés attracted fewer German Wehrmacht officers than the cafés in Montparnasse, so the writers and thinkers working there were more or less left to their own devices.

On the recommendation of his wife–de Beauvoir–Jean-Paul Sartre starting frequenting Café de Flore in 1941, coming after a few months in the French army and a detention camp in Germany. The couple made the first floor of the Flores their headquarters during the day and a meeting room at night. Sartre’s and de Beauvoir’s fame evolved during the time they were entrenched at Café de Flores.

“We are completely settled there; from nine o’clock in the morning until midday, we work, we eat, and at two o’clock we come back and chat with friends until eight o’clock. After dinner, we see people who have an appointment. That may seem strange to you, but we are at home.” Jean-Paul Sartre

At the end of the war, the cafe became the heart of artistic and intellectual life in Paris. Sartre and de Beauvoir were joined in the late 1940s by Arthur Koestler, Truman Capote and Lawrence Durrell. The most famous names were Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus, whose every thought on art, morality, literature and politics commanded international attention and Simone de Beauvoir, whose writings went on to change the world – and continue to do so – in a far more definitive way than Camus, Sartre or any other of the leading male intellectuals of the period.

It was an unusual confluence of politics, philosophy, art and literature, all concentrated in a relatively small area of the Left Bank of Paris that gave rise to the cafes of ‘La Rive Gauche’ representing European cosmopolitanism and as a forum for discourse.

Endnote

- In 1958 Beach announced she was giving the name of her shop to George Whitman, a former journalist and ex-serviceman who had opened a bookshop modelled on hers and in 1964, on the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s birth, Whitman officially renamed his bookshop Shakespeare and Company in honour of Beach and the original store.

Image attribution: Photo by

Sources: Andrew Hussey, How postwar Paris became the intellectual capital of the world, New Statesman America May 2018.